Daryl Wright has witnessed, first-hand, the positive effects that youth development programs can have on children and our society as a whole. Wright discusses his experiences as a youth worker and the importance of leadership development.

I’ve had the privilege to participate and bear witness to a number of stories of youth leadership. These are composites of some of the true stories I experienced during my career as a youth worker. Over the past several decades, I’ve had the privilege to witness hundreds of young people take leadership in their communities. I have seen how these opportunities transformed their lives. I believe in leadership development as a critically important aspect of youth work.

Different approaches in youth work

Youth workers are employed in a range of settings that are shaped by different approaches to make a difference in young people’s lives. Some of us work within groups funded by state agencies that focus on youth and family health services, for example. Here, youth workers are either intervening in the lives of young people in need or preventing young people from getting involved in dangerous situations through an educational approach. The youth services approach emphasizes treatment and prevention. Service providers are non-judgmental and services are accessible to all adolescents who are in need, meet the expectations, and address the needs of youthful clients (World Health Organization, 2012). Youth workers also work for youth development programs such as YMCAs or Boys and Girls Clubs. These are usually Out-of-School Time (OST) programs. These programs hire staff who succeed in creating positive settings for young people. Successful programs are characterized by physical and psychological safety, appropriate structure, supportive relationships, opportunities to belong, positive social norms with support for personal effectiveness and include opportunities for skill building, and integration of family, school and community efforts. Young people have ready access to supportive relationships with adults and peers, challenging and engaging activities and learning experiences, and meaningful opportunities for involvement1.

Areas of leadership development

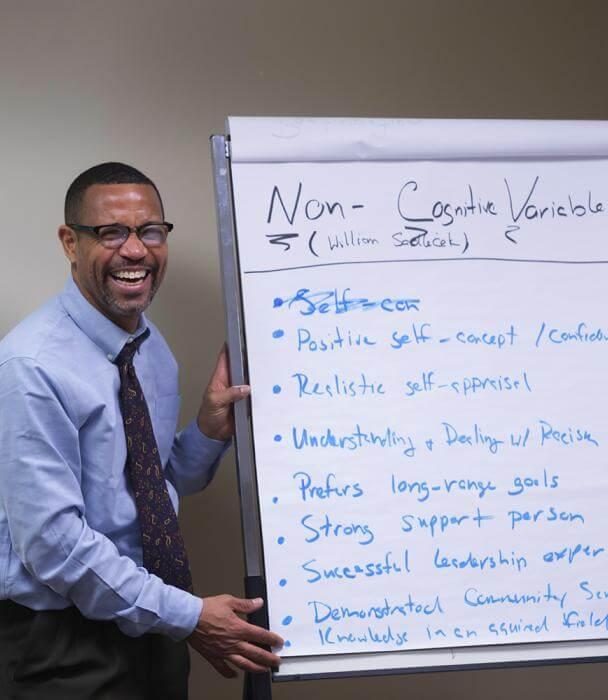

Leadership development can extend youth services and youth development approaches when it focuses on youth identity development, youth organizing, community service, and youth involvement in decision making. Leadership development is a means of counteracting the systemic disrespect and marginalization that young people may experience as a result of being members of marginalized groups in our society or living in low-income communities— urban or rural (Stoneman, 2010). In this regard, leadership development cultivates and unleashes the creative intelligence that lies within every young person (Stoneman and Bell, 2000). Staff who implement the leadership development approach work with young people in three areas, simultaneously: personal leadership, which fosters identity formation; organizational leadership, which builds upon the role of youth as decision-makers; and community leadership, which focuses on the role of youth as catalysts for change1.

Leadership Development engages young people

In my experience, the central problem of youth work is engagement. When young people are engaged in youth programs, they show up and they remain involved for long periods of time. This is an indication that young people are getting something out of the program. Young participants are motivated to be involved and grow as a result of their participation. While youth development focuses on the individual development of young people, leadership development challenges young people to think beyond themselves by taking action that empowers them and their communities. They are also placed in positions to advocate for change by interacting with decision-makers within systems that may be sources of marginalizing experiences (Edwards et. al., 2003). For example, Young Voices in Providence, Rhode Island is a program comprised of students attending public high schools in the city. Youth-designed and carried out a survey of nearly 1,000 students about how they experienced public high school environments. They compiled the results and prepared recommendations to increase attendance and graduation rates at a public meeting with the superintendent of Providence Public Schools and district leaders.

Leadership Development Works!

Leadership Development activities build skills while affirming a sense of identity and agency among youth. Studies have shown that programs that provide leadership opportunities increase the retention of middle and high school aged youth in out-of-school programs (Deschenes et. al., 2010) and organizations that promote civic activism and youth organizing are able to successfully recruit and retain older youth 16-23 years of age2.

Trauma-informed practice has emerged as an important part of the ongoing discourse about youth work practice. Young people may be affected by a traumatic family crisis or community violence, for example. Creating conditions for young people to heal and promote social-emotional growth is critically important. Yet, even social-emotional learning is “incomplete without engaging young people in actions necessary to improve quality of life” At ROCA (Reaching Out to Chelsea Adolescents) in Massachusetts, for example, peacemaking circles have been used as a method for young people address the trauma in their lives and promote community change 3.

Adult youth workers play important roles

All youth workers, whether they are interacting directly with youth or administering these programs, are in privileged positions to create conditions for young people to heal, develop, and transform their lives and communities. Skilled youth workers can be facilitators and voices of reality to bring out young people’s best thinking. Effective youth workers operate with profound respect and openness to young people and a principled willingness to confront young people when they are engaging in negative or destructive behavior. They are also mindful of how they use their presence to ensure the right balance between supporting young people and providing opportunities for them to make their own mistakes and learn from them. Love and a spirit of learning lay at the foundation of this work.

My experience as a martial artist has also shaped my view of leadership development as a practice. In order to get better at martial arts, I come to the practice hall several times a week. I get feedback on what I’ve done well and what I could improve. I work at what I need to improve upon in spare moments, returning to the practice hall again, repeating the ritual.

We get better and better at creating conditions for leadership as we engage in the practice of cultivating the leadership of young people— for their lives, their families, their communities, and the world. This can be incredibly creative and energizing for youth workers. This practice invites us to use our energies in service to the world. Working with young leaders on local efforts and with youth workers around the world has reinforced my belief that this is true.

1. Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development, Learning and Leading: A Tool Kit for Youth Development and Civic Activism, 2004.

2. Ginwright, Shawn Hope and Healing in Urban Education: How Urban Activists and Teachers are Reclaiming Matters of the Heart Routledge, Taylor and Francis Publishers, 2016.

3. Boynes-Watson, Carolyn Peacemaking Circles and Urban Youth: Bringing Justice Home, Living Justice Press, 2008.

About the author

Daryl Wright

Daryl Wright is Principal Consultant with Knight Consulting, LLC, a former Vice President at Youth Build USA, and an adjunct faculty member with Springfield College PCS. He has experience in youth development, community development, and workforce development. He has worked with the community-based organizations, unions, business associations and employers developing innovative programs and taking them to scale. He is the author of 50 publications. Daryl has a master’s degree in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning from Tufts University. He is a serious practitioner of the Japanese martial arts and is a 3rd-degree black belt in Jut Jit Su. He is married and has one daughter.